I was originally going to make this about dinosaurs, but I just knew someone would say, "But my favorite is elasmosaurus  " or whatever and be sad because it is not a dinosaur. And then I realized I wanted to mention stuff that wasn't Mesozoic and probably other people would to soooo... here we are. I am thinking basically anything over, like, 5000-ish years old. Or something. I'm not really being more precise about my standards here beyond a vague "pre-modern."

" or whatever and be sad because it is not a dinosaur. And then I realized I wanted to mention stuff that wasn't Mesozoic and probably other people would to soooo... here we are. I am thinking basically anything over, like, 5000-ish years old. Or something. I'm not really being more precise about my standards here beyond a vague "pre-modern."

This topic was prompted by my reading The Complete Dinosaur, The Second Edition, which is absolutely amazing. It's basically a broad overview of the dinosaurs with chapters about the history of dinosaur discoveries, their taxonomic classification, their relation to birds (an entire chapter entirely dedicated to birds themselves after the chapter on Theropods), their skeletons, musculature, and paleoneurology, various suborders / infraorders in Dinosauria, and so forth. It is basically an overview of scientific information for an educated lay audience, and it includes three or four pages of reference material to the relevant journal articles for the relevant articles referenced in the chapter.

I also enjoy some of the arguments. For instance, there are two chapters that appear back-to-back. Chapter 36 is entitled "Metabolic Physiology of Dinosaurs and Early Birds", and it argues vociferously that, for a variety of reasons, dinosaurs were not actually endothermic but are actually ectothermic in their routine, metabolic and lung ventilation rates, but nonetheless may also have possessed the capacity for sustained activity close to that of endotherms. It seemed reasonable at first, though what I learned in the subsequent chapter has me rather skeptical again. They were very forceful in their claims, and if their insistence that various claims "strain credulity" and "should invite skepticism" weren't enough, they also close their penultimate section with, "Finally, claims elsewhere in this volume of putative falsification of our conclusions that theropods lacked respiratory turbinates (see Paul) amount to little more than a series of statistically unsupported anecdotes."

The next chapter? "Evidence for Avian-Mammalian Aerobic Capacity and Thermoregulation in Mesozoic Dinosaurs", which I am currently in the middle of reading. I find it very interesting and I wonder how the authors of the previous chapter would reconcile some of the issues he's bringing up regarding the differences in behaviors of endothermic and ectothermic animals - to the point where an ectothermic animal might well kill itself in trying do behave like an endothermic animal - and the fact that dinosaurs' behavior seems to much more closely resemble endothermic animals in terms of sustained casual speeds, socialization, parenting, and so forth. And of course, he is also similarly entertaining in his commentary on the previous chapter. For instance, "The arbitrary dismissal of the often capacious NA (nasal airways) of ornithischians as evidence for the presence of well-developed RC (respiratory conchae) by Ruben et al. (2003) indicates that they do not consider their own methodology reliable when it produces results contradictory to their concept of dinosaur energetics."

It does contain a few unfortunate accuracies, though. For instance, it makes the claim that, "Despite the appeal of Tyrannosaurus, the ubiquity of Triceratops, or the stateliness of Stegosaurus, sauropods are the iconic dinosaurs." This is utter nonsense, of course. Tyrannosaurus rex is the iconic dinosaur and has been since its discovery, no matter what that silly hadrosaur-loving, Spinosaurus-overhyping, T.rex-is-a-scavenger propagandist Horner says. Speaking of Horner, I did particularly enjoy this caption to a picture of two skulls:

Damn right, they do.

Anyway, some of my favorites, both all-time and more recent:

Tyrannosaurus rex

I'm sure everyone is shocked.

I actually went through a bit of a period of being sort of over T. rex - too slow, too dumb, possibly more of a scavenger, and not even the biggest! - but then I saw this wonderful post (I just read Holtz's paper before making this post ). There's also been all sorts of cool stuff about T. rex in recent years. For instance, there was the news its weight may have been underestimated by 30 percent (which inspired the picture above), the fact that the size of the muscles in the tail, particularly the cardofemoralis, may have been underestimated by as much as 45 percent, or that its bite was significantly stronger than those specious "only as strong as an alligator haha" claims that were probably based on feeding bites and not actual maximum capacity. And it was smarter than any other theropod of a similar size (e.g. smart enough to figure out that Triceratop's horns are scary and biting them off is a good idea), as well as faster, and with a significantly more robust build, skull, and neck muscles.

). There's also been all sorts of cool stuff about T. rex in recent years. For instance, there was the news its weight may have been underestimated by 30 percent (which inspired the picture above), the fact that the size of the muscles in the tail, particularly the cardofemoralis, may have been underestimated by as much as 45 percent, or that its bite was significantly stronger than those specious "only as strong as an alligator haha" claims that were probably based on feeding bites and not actual maximum capacity. And it was smarter than any other theropod of a similar size (e.g. smart enough to figure out that Triceratop's horns are scary and biting them off is a good idea), as well as faster, and with a significantly more robust build, skull, and neck muscles.

There may be some fragmentary theropods that could possibly be slightly longer or slightly heavier but none of them have the combination of speed, intelligence, durability, anatomical sophistication or biting strength that T. rex did.

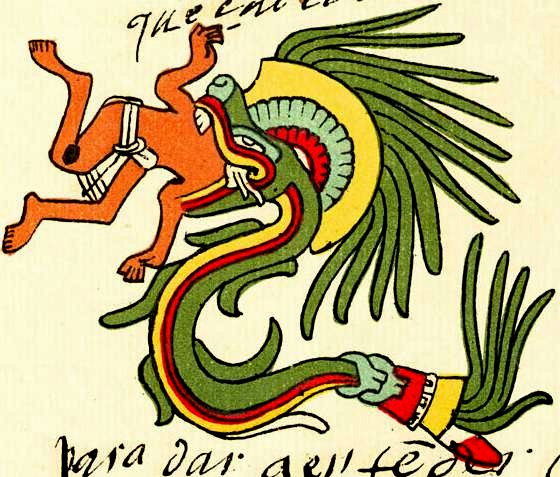

Queztalcoatlus

When I was a kid, my parents took me to the Children's Museum in Indianapolis (and it is a fantastic museum and fun for all ages, go now, etc. - I went for the first time since I was a pre-teen just last year and it was a fantastic experience even though I hardly saw half of it due to time constraints) pretty regularly, and one of my favorite parts was this gigantic pterosaur they had hanging in the ceiling. I think it was a Queztalcoatlus, but it's been so long that I don't know if that's just the name I am ascribing to it because of how huge it was or if that's actually accurate.

In any case, I thought they were very cool, until I started reading how some scientists doubted they could even achieve powered flight and how they would have been reliant on cliffs and gliding and thermals in order to stay aloft. And that just sounds, well, lame. Who cares about an oversized reptilian albatross who would get eaten by the first theropod that manages to sneak up on it before it could waddle up to speed and off a cliff? But more recently I have read some really exciting stuff - great increases in their weight estimates, but also suggestions that they could launch themselves into the air using their powerful forelimbs to speeds of 35 MPH in mere moments (compared to a vampire bat) without relying on running starts (as in the modern albatross or leaping off of cliffs, sustained flight "up to 80 miles an hour for 7 to 10 days at altitudes of 15,000 feet" and a maximum flight range of 8,000 - 12,000 miles. Just imagining a 30-something wingspan and giraffe-height 400 - 500 pound animal soaring at those speeds is exciting.

Of course, I also read Debbie Downers who are skeptical about some or all of those elements, but I'll continue to find it interesting until I read something more conclusive that it isn't accurate!

Deinonychus

(I actually liked the design of them in the Clash of the Dinosaurs: Perfect Predators, but I couldn't find a good picture)

I have always found Deinonychus to be the Goldilocks of the raptors. Velociraptor was too small; Utahraptor seemed too big for how I imagined it in my head. Deinonychus always seemed just right to me. It had sort of gone down in my estimation after learning that apparently the claw was not very good for slashing or tearing (though more about that), they weren't built for particularly fast speeds, and they weren't nearly as intelligent as I had imagined them to be as a kid. But I have learned, taht while they evidently weren't super fast, they were evidently built for extremely agile running due to their stiff and thin tail that was capable of rapid rotational speeds - the distal four-fifths of the tail are sheathed in bony rods that are elongated postzygapophyses (zygapophyses are extensions from a vertebrae that fit in with the next one; I think from context postzygapophyses are structures which extend beyond that and prezygapophyses extend towards earlier vertebrae; maybe someone who is better at anatomy can explain if I'm misunderstanding), and this creates the very stiff tail.

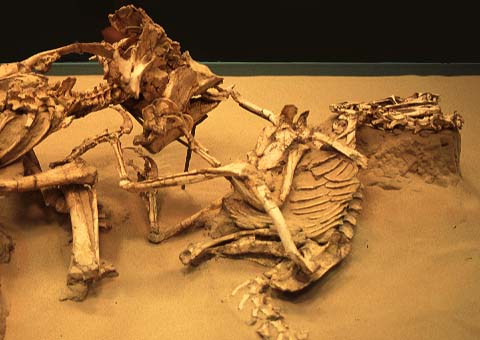

Going back to the claws for a moment, the raptors evidently did still use their claws offensively (e.g. the famous fighting dinosaurs fossil), and I seem to remember that in the test I saw of the claw, it was only the strike using the leg itself and the tendon. However, in the book it mentions that, given their evident agility, one could imagine them leaping onto their prey and using their body weight to drive their claws in, and then using their weight to draw the claws down along the body of the prey. Maybe this would be more feasible; the pure "leg strike" I remember seeing did not seem very feasible as an attacking strategy considering the limited puncture depth and apparently superficial damage. And there was also something about them using the claws for climbing up prey, as the claws would be capable of supporting the weight.

As for feathers: I have always I found the lithe appearance very appealing, and now that I'm over the "It doesn't look like what I imagined " phase, I am finding some of the designs really interesting.

" phase, I am finding some of the designs really interesting.

Titanoboa

I just watched the Smithsonian mini-documentary about this snake (though I also remember the GAF topic about the model that was the inspiration for the episode), and it is fascinating. The green anaconda has always been my favorite living snake, and this is essentially that snake on an incredibly supersized scale. Just imagining a nearly 50 foot snake swimming around the prehistoric Amazon (or whatever river might have been around then, I don't really know come to think of it) and capable of eating 20 foot crocodiles is mind-blowing.

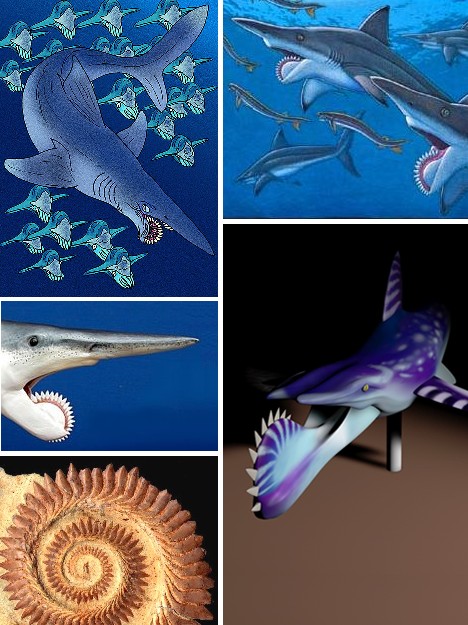

Others: Titanis walleri, Ankylosaurus (and Euoplocephalus) (these are some of my all-time favorites but this post is too long as is!), Smilodon, Titanis walleri, Megalograptus (largest arthropod ever at 6 feet, very cute, and apparently innovated a lot of stuff later and smaller predatory arthropods would use), Cave Mammals (Lions, Bears, etc), Dunkleosteus (20 - 30 feet long, armor-plating, and teeth made of boney plates like a cleaver combined with one of the strongest bites of any fish and almost certainly the strongest for a non-shark), Megalodon, Elasmotherium sibiricum (look at that horn!), Doedicurus clavicaudatus (it takes an akylosaurian tail club and makes it spiky - what could be better? Well, besides a tail that would actually be useable for defense, I suppose), Irish Elk

I could go on but it's getting harder to remember what they looked like and then trying to figure out names by Googling my vague descriptions. :x

This topic was prompted by my reading The Complete Dinosaur, The Second Edition, which is absolutely amazing. It's basically a broad overview of the dinosaurs with chapters about the history of dinosaur discoveries, their taxonomic classification, their relation to birds (an entire chapter entirely dedicated to birds themselves after the chapter on Theropods), their skeletons, musculature, and paleoneurology, various suborders / infraorders in Dinosauria, and so forth. It is basically an overview of scientific information for an educated lay audience, and it includes three or four pages of reference material to the relevant journal articles for the relevant articles referenced in the chapter.

I also enjoy some of the arguments. For instance, there are two chapters that appear back-to-back. Chapter 36 is entitled "Metabolic Physiology of Dinosaurs and Early Birds", and it argues vociferously that, for a variety of reasons, dinosaurs were not actually endothermic but are actually ectothermic in their routine, metabolic and lung ventilation rates, but nonetheless may also have possessed the capacity for sustained activity close to that of endotherms. It seemed reasonable at first, though what I learned in the subsequent chapter has me rather skeptical again. They were very forceful in their claims, and if their insistence that various claims "strain credulity" and "should invite skepticism" weren't enough, they also close their penultimate section with, "Finally, claims elsewhere in this volume of putative falsification of our conclusions that theropods lacked respiratory turbinates (see Paul) amount to little more than a series of statistically unsupported anecdotes."

The next chapter? "Evidence for Avian-Mammalian Aerobic Capacity and Thermoregulation in Mesozoic Dinosaurs", which I am currently in the middle of reading. I find it very interesting and I wonder how the authors of the previous chapter would reconcile some of the issues he's bringing up regarding the differences in behaviors of endothermic and ectothermic animals - to the point where an ectothermic animal might well kill itself in trying do behave like an endothermic animal - and the fact that dinosaurs' behavior seems to much more closely resemble endothermic animals in terms of sustained casual speeds, socialization, parenting, and so forth. And of course, he is also similarly entertaining in his commentary on the previous chapter. For instance, "The arbitrary dismissal of the often capacious NA (nasal airways) of ornithischians as evidence for the presence of well-developed RC (respiratory conchae) by Ruben et al. (2003) indicates that they do not consider their own methodology reliable when it produces results contradictory to their concept of dinosaur energetics."

It does contain a few unfortunate accuracies, though. For instance, it makes the claim that, "Despite the appeal of Tyrannosaurus, the ubiquity of Triceratops, or the stateliness of Stegosaurus, sauropods are the iconic dinosaurs." This is utter nonsense, of course. Tyrannosaurus rex is the iconic dinosaur and has been since its discovery, no matter what that silly hadrosaur-loving, Spinosaurus-overhyping, T.rex-is-a-scavenger propagandist Horner says. Speaking of Horner, I did particularly enjoy this caption to a picture of two skulls:

32.5 "Rex Rules!" The wide temporal region and broad muzzle of Tyrannosaurus gives this animal and exceptionally strong skull. The long, low, slender snout of Suchomimus makes for a much weaker skull. The robust teeth of Tyrannosaurus are associated with a very deep, thick maxilla, and are indicative of a very powerful bite. The relatively small teeth of Suchomimus are rooted in a slender, thin maxilla, and it is highly unlikely that this animal was capable of biting with great force. The slender, weak skulls seen in spinosaurids such as Suchomimus contradict aspects of the plot in the film Jurassic Park III

Damn right, they do.

Anyway, some of my favorites, both all-time and more recent:

Tyrannosaurus rex

he's not fat; he's thick

I'm sure everyone is shocked.

I actually went through a bit of a period of being sort of over T. rex - too slow, too dumb, possibly more of a scavenger, and not even the biggest! - but then I saw this wonderful post (I just read Holtz's paper before making this post

There may be some fragmentary theropods that could possibly be slightly longer or slightly heavier but none of them have the combination of speed, intelligence, durability, anatomical sophistication or biting strength that T. rex did.

Queztalcoatlus

When I was a kid, my parents took me to the Children's Museum in Indianapolis (and it is a fantastic museum and fun for all ages, go now, etc. - I went for the first time since I was a pre-teen just last year and it was a fantastic experience even though I hardly saw half of it due to time constraints) pretty regularly, and one of my favorite parts was this gigantic pterosaur they had hanging in the ceiling. I think it was a Queztalcoatlus, but it's been so long that I don't know if that's just the name I am ascribing to it because of how huge it was or if that's actually accurate.

In any case, I thought they were very cool, until I started reading how some scientists doubted they could even achieve powered flight and how they would have been reliant on cliffs and gliding and thermals in order to stay aloft. And that just sounds, well, lame. Who cares about an oversized reptilian albatross who would get eaten by the first theropod that manages to sneak up on it before it could waddle up to speed and off a cliff? But more recently I have read some really exciting stuff - great increases in their weight estimates, but also suggestions that they could launch themselves into the air using their powerful forelimbs to speeds of 35 MPH in mere moments (compared to a vampire bat) without relying on running starts (as in the modern albatross or leaping off of cliffs, sustained flight "up to 80 miles an hour for 7 to 10 days at altitudes of 15,000 feet" and a maximum flight range of 8,000 - 12,000 miles. Just imagining a 30-something wingspan and giraffe-height 400 - 500 pound animal soaring at those speeds is exciting.

Of course, I also read Debbie Downers who are skeptical about some or all of those elements, but I'll continue to find it interesting until I read something more conclusive that it isn't accurate!

Deinonychus

(I actually liked the design of them in the Clash of the Dinosaurs: Perfect Predators, but I couldn't find a good picture)

I have always found Deinonychus to be the Goldilocks of the raptors. Velociraptor was too small; Utahraptor seemed too big for how I imagined it in my head. Deinonychus always seemed just right to me. It had sort of gone down in my estimation after learning that apparently the claw was not very good for slashing or tearing (though more about that), they weren't built for particularly fast speeds, and they weren't nearly as intelligent as I had imagined them to be as a kid. But I have learned, taht while they evidently weren't super fast, they were evidently built for extremely agile running due to their stiff and thin tail that was capable of rapid rotational speeds - the distal four-fifths of the tail are sheathed in bony rods that are elongated postzygapophyses (zygapophyses are extensions from a vertebrae that fit in with the next one; I think from context postzygapophyses are structures which extend beyond that and prezygapophyses extend towards earlier vertebrae; maybe someone who is better at anatomy can explain if I'm misunderstanding), and this creates the very stiff tail.

Going back to the claws for a moment, the raptors evidently did still use their claws offensively (e.g. the famous fighting dinosaurs fossil), and I seem to remember that in the test I saw of the claw, it was only the strike using the leg itself and the tendon. However, in the book it mentions that, given their evident agility, one could imagine them leaping onto their prey and using their body weight to drive their claws in, and then using their weight to draw the claws down along the body of the prey. Maybe this would be more feasible; the pure "leg strike" I remember seeing did not seem very feasible as an attacking strategy considering the limited puncture depth and apparently superficial damage. And there was also something about them using the claws for climbing up prey, as the claws would be capable of supporting the weight.

As for feathers: I have always I found the lithe appearance very appealing, and now that I'm over the "It doesn't look like what I imagined

Titanoboa

I just watched the Smithsonian mini-documentary about this snake (though I also remember the GAF topic about the model that was the inspiration for the episode), and it is fascinating. The green anaconda has always been my favorite living snake, and this is essentially that snake on an incredibly supersized scale. Just imagining a nearly 50 foot snake swimming around the prehistoric Amazon (or whatever river might have been around then, I don't really know come to think of it) and capable of eating 20 foot crocodiles is mind-blowing.

Others: Titanis walleri, Ankylosaurus (and Euoplocephalus) (these are some of my all-time favorites but this post is too long as is!), Smilodon, Titanis walleri, Megalograptus (largest arthropod ever at 6 feet, very cute, and apparently innovated a lot of stuff later and smaller predatory arthropods would use), Cave Mammals (Lions, Bears, etc), Dunkleosteus (20 - 30 feet long, armor-plating, and teeth made of boney plates like a cleaver combined with one of the strongest bites of any fish and almost certainly the strongest for a non-shark), Megalodon, Elasmotherium sibiricum (look at that horn!), Doedicurus clavicaudatus (it takes an akylosaurian tail club and makes it spiky - what could be better? Well, besides a tail that would actually be useable for defense, I suppose), Irish Elk

I could go on but it's getting harder to remember what they looked like and then trying to figure out names by Googling my vague descriptions. :x