Because it didn't fit in the title, this will SPOIL aspects of BOTH GAMES, if that's something you're concerned about.

2017 saw the release of two remakes of the divisive, experimental second entries of long-running Nintendo series on the 3DS - Fire Emblem Echoes: Shadows of Valentia, and Metroid: Samus Returns; taking their inspiration from Fire Emblem Gaiden and Metroid II: Return of Samus - both originally released in 1991. How these two games, from very different developers (Intelligent Systems, the studio responsible for the Fire Emblem series through its inception; and Mercury Steam, on their first foray into the Metroid franchise) variously approached their source material is interesting to compare and contrast.

SYSTEMS & GAME DESIGN

The first aspect which can be compared between the two is their take on the unique game structure and individual design decisions of the source games, as well as how they went about 'modernising' those quirks, both in relation to other entries within the series and the industry in general.

Echoes' faithfulness towards Gaiden's systems runs from broad design decisions - such as the near-exact replication of map design, focus on a world map structure, visitable towns and explorable dungeons - to smaller details such as magic being cast from health, the increased archer range (and 1-space counterattack) compared to the rest of the series, as well as broadly consistent statistical growth rates, the usage of an accurate instead of fudged displayed hit percentage (which the series abandoned in favour of the current approach with the GBA games), unique boss characteristics and weaknesses (the boss Jedah's having a specific order to which he must be attacked to receive damage, and the final boss falling to a specific low-level spell instead of the god-slaying Falchion) as well as the dread fighter to villager reclassing loop. The innovations and refinements to this structure were built on the base of surprising faithfulness to the original game - such as additional skills learned by classes or from weapons to add greater tactical depth to combat, boosts to the aforementioned statistical growth rates which still fell broadly in line with those of the original game, the inclusion of the 'Mila's Turnwheel' function which allowed player actions to be reversed to compensate for bad luck or hasty decisions, and inclusion of later series staples such as support conversations, playing without permanent unit death and base conversations. As such; while the game allowed for something resembling the original design philosophy of Gaiden to shine through, its faithfulness could also be argued to be a weakness - the extremely simplistic map design often cited as an example where a radical revision may have been in order.

Samus Returns can be compared along those lines - the 1991 original diverged from the first in the series through its focus on discrete, sequential areas over one continuous labyrinth, and structured itself around the hunt for 40 Metroids, the counter prominently displayed in the game UI throughout. These aspects were all reflected in the 3DS game, with additional refinements to bring things in line with modern series conventions - i.e., a map, diagonal aiming, fast travel and elevator cutscenes. However, on a moment-to-moment and core map design level, Samus Returns displays notable differences. Some of these disparities are purely to do with the technical limitations of the original title on the Gameboy - such as the zoomed-in field of view and monochrome palette, which give the original a specific, albeit unintended, atmosphere not shared by later titles. However, the fundamental flow of combat and navigation are also affected by three new additions new to 2D Metroid in general - 360 degree free aiming, Aeion abilities, and the melee counter mechanic. In particular, the early game encourages a reliance on the counter mechanic, with regular enemy health increased to match - this has drawn complaints for being a repetitive and obstructive gameplay device which needlessly slows the player down, but also praise for varying the strategy and pacing of basic gameplay from the now-staple 2D Metroid progression of beam spam to obliterating everything with the Screw Attack with little nuance in between. Likewise, the precision afforded by the aiming mechanic in boss fights and the way it forces a decision between movement and offense is a further tangible change in direction. Similarly, while hewing close to the original game's structure of linearly cleared, discrete sectors, the actual level design also displays changes in this regard - while maintaining the original's cavernous rooms in some respects, the freedom of movement with the wall-climbing Spider Ball is more often restricted, and paths are blocked with a higher degree of upgrade-specific barriers and blocks, along with an increased incidence of one-way or locked doorways. In this case, the deviation from the original while using the same base of ideas is apparent - the question more falls on whether the more focused and guided gameplay experience is superior - and in terms of the combat changes, whether the current approach offers a more enjoyable style of approaching the genre.

ARTWORK & ART DIRECTION

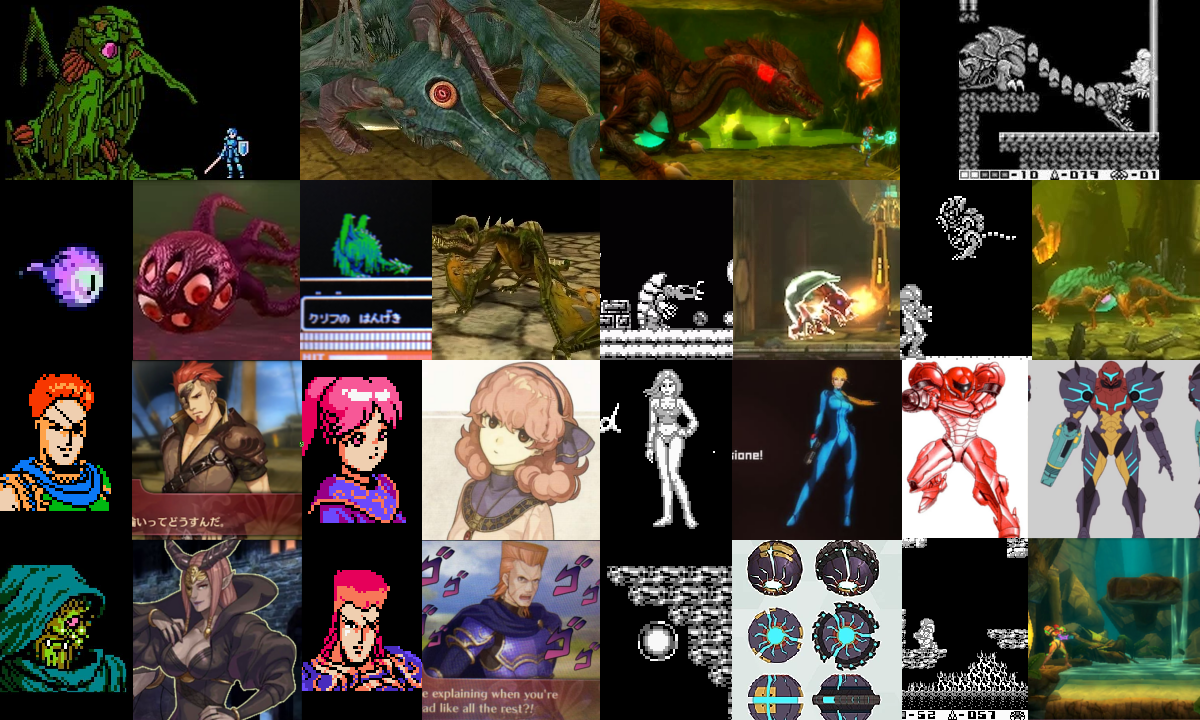

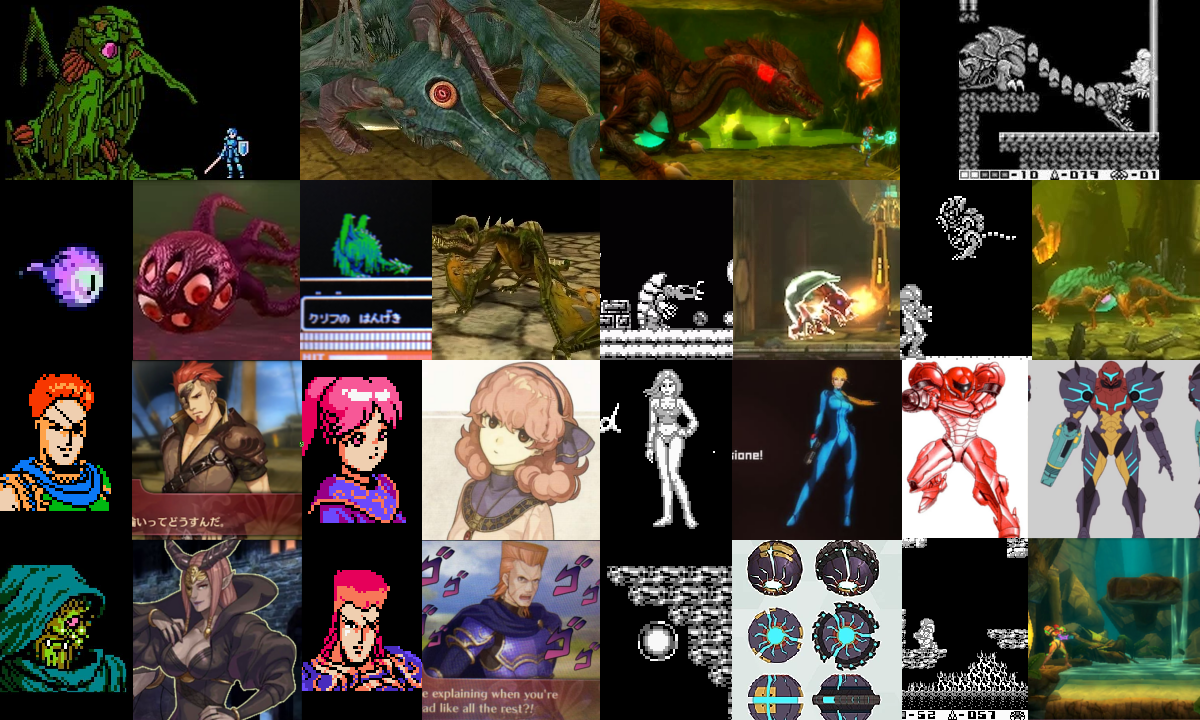

When comparing the artwork of the two games, the contrasting nature of the Fire Emblem and Metroid franchises is most apparent - as the former is largely not bound to the same set of returning protagonists and supporting cast members (with few exceptions), there exists a far greater scope for reinterpretation - particularly where Gaiden's rather amorphous and inconsistent designs are concerned. While references were frequently made to the original artwork, the sometimes-radical departures from the Gaiden sprites were near-unanimously seen as improvements - as the job here was to essentially create characters from whole cloth, rather than iterating on firmly established lines. Where a comparison to Metroid can be drawn is the way it interpreted the designs of its enemies and monsters - the Mogall and Necrodragon display conservative iterations on their original sprites and later series appearances, while the choice of a more conventional dragon form for the previously muculent Duma was still done within reasonable bounds of the established material, taking care to highlight his decayed nature and solitary laser eye.

These creature designs are similar to the revisions undertaken for Samus Returns' Metroid forms - notably present in the Zeta Metroid's shift from a squatter, bipedal form to a lankier distribution of the same features in a more xenomorph-inspired frame, and the Omega Metroid's shift to a sleeker body shape which notably reduces its oversized head seen in its cameo appearance as the 'final boss' of Metroid Fusion. Like the alterations to Duma, these design changes aid in presenting the creatures as more visually formidable antagonists (especially taking into account the more visible variance in size) - and while it can be argued that the new designs diminish some of the original material's uniqueness, they seem to generally be well-received as modernisations. The character design, as mentioned above, takes a completely different approach due to both the nature of the Metroid series and Metroid II's place within it - unlike Gaiden, whose characters remained mostly obscure afterthoughts open to complete reinterpretation, Metroid II defined the modern image of Samus, from the general shape and structure of the suit to the now-iconic Varia shoulder pads. As such, the task faced by Samus Returns was not one of reinvention, but embellishment. That can be seen throughout its designs for Samus - keeping to the established template of the character, while adding in various additional details and aspects taken from throughout the series - an iteration of the now-standard Zero Suit as it appeared in Other M with minor colour alterations being the most visible, but also a visor with the same profile as that of the Prime Trilogy's Dark Samus, Metroid Prime's blue-accented Gravity Suit, large visible treads for the Spider Ball and a denser distribution of light strips throughout the suit.

However, while the character designs may be conservative, the environmental art of Samus Returns displays a massive change. Return of Samus was a monochrome Gameboy title with essentially no background detail at all, while Samus Returns' most striking visual details are its colourful, vibrant and animated 3D backgrounds, leaning towards the bright palette of Zero Mission and Other M. The change in presentation (and especially atmosphere) cannot be overstated - the tone of the game completely changes when moving between the monochrome simplicity of the Gameboy and Samus Returns' approach. This is another area in which taste can be seen to differ - while the increased visual feedback and interest of these additions is essential for a modern title, the degree to which they provide a livelier and brighter take on SR388 is considered a step down for those who found the original's limitations created a memorably tense and dread-filled experience.

MUSIC

Title (Metroid II) / Title (Metroid II)

Metroid Boss (Metroid II) / Omega Metroid (Samus Returns)

Chozo Ruins (Metroid II) / Chozo Ruins (Return of Samus)

Queen Metroid (Metroid II) / Queen Metroid (Samus Returns)

Vs. Duma (Gaiden) / A Fell God's Tempest (Echoes)

Land of Sorrow (Gaiden) / A Song for Bygone Days (Echoes)

Tower (Gaiden) / The Pinnacle of False Belief (Echoes)

Final Map (Gaiden) / Twilight of the Gods (Echoes)

Metroid II's soundtrack may be more of an outlier among the larger series than even its general structure and presentation - eschewing the melodic and memorable background tracks the series is known for, its area themes largely trend towards ambience and border in places on atonality. While Samus Returns does feature several arrangements of Metroid II's music, such as the 'Tunnel' theme, an atmospheric take on the Chozo Ruins track and a cover of the Baby Metroid theme, it largely deviates from the Metroid II soundtrack, whether with original material or covers of tracks from elsewhere in the series - prominently using the Lower Norfair, Theme of Samus and Brinstar (Red Soil) cues as well as the expected Ridley boss theme; in addition, the game's version of the title theme foregrounds the original Metroid theme before including elements of Metroid II's own title theme. Considering the nature of Metroid II's music, this liberal approach making significant use of popular tracks from the rest of the series would seem to be justified in pursuit of producing a recognisable 'Metroid' soundtrack - while also retaining some elements of the original game's approach in the use of primarily atmospheric music.

Fire Emblem Gaiden's soundtrack was not nearly the departure from series standards Metroid II's was, and as such integrating it into a modern remake in line with recent franchise games was not as difficult a task, however the comprehensiveness of the approach taken towards the original soundtrack is an interesting contrast. No tracks from the original game were left out, regardless of their seeming incompatibility with the most recent games in the series - such as the use of several distinct world map themes when compared against Fire Emblem Awakening's short world map jingle and Fire Emblem Fates' silent world map, the return of separate battle themes after Awakening and Fates' adoption of dynamic music; and retaining the final boss' chaotic map theme-interrupting track as opposed to going with playing a single map theme throughout as with both aforementioned games. Also worthy of note is the way in which Echoes builds on the leitmotifs of the original Gaiden score alongside original music, most notably in 'Lord of a Dead Empire' and 'Sacrifice and the Saint'.

Meanwhile, Samus Returns' more distant relationship with its source material results in several pieces from Metroid II being left out entirely, and avoids turning the original soundtrack's themes into longer-running leitmotifs through its preferential use of motifs established elsewhere in the series. This lack of 'faithfulness' is by no means a negative thing, however, as it does allow the game more freedom in terms of sound design, while decisions such as the use of a separate battle theme in Echoes could frequently feel like a pointless step back, a replication of tradition for tradition's sake. Original themes for each Metroid form further accentuate their progression, and while the use of music decoupled from individual areas (e.g. Lower Norfair in every superheated room) is a significant departure from previous games, it does fit Samus Returns' reduced emphasis on backtracking and effectively stage-based design which leaves less room to intimately characterise each area.

NEW STALKERS & OLD RIVALS

As a final point, both games' handling of a storied remake expectation - entirely new content and series continuity - serve as an interesting parallel. While as a RPG, Echoes' far more present storytelling and full voice acting can't be compared to a story-light Metroid title through basic structure, the way these additional elements are introduced in relation to the original games does create an interesting contrast. Along with new threats throughout the main bulk of the storyline (the ever-present Diggernaut in Samus Returns, the new antagonist Berkut in Echoes) and backstory additions in line with series mythology (the clarification of Mila and Duma's nature as Divine Dragons and the looming threat of Grima; plus his newly created backstory, alongside the references to Metroid Fusion's X in Samus Returns, as well as the ominous introduction of the Chozo civil war) Echoes and Samus Returns also feature a final 'bonus' boss who appears elsewhere in the series - for Echoes, a nascent form of Fire Emblem Awakening's Grima, and Samus Returns the near-omnipresent Ridley.

Where this differs most is in how this element is treated - it is impossible to fight Grima in Echoes before the credits run, and the 'Labyrinth of Thabes' in which he appears is firmly treated as a dubiously canonical postscript. Meanwhile, Ridley's appearance in Samus Returns is a mandatory part of the finale - he's now the actual final boss; not an extra challenge for a higher difficulty mode, certain completion time or percentage. It's a fascinating difference in how Samus Returns and Echoes exist in relation to their source material that a game far lighter on story content and additional narrative is the one which made the decision to make such a central change.

In any case, Samus Returns did get away with a much neater title - "Fire Emblem Echoes: Shadows of Valentia" will always be a mess.

2017 saw the release of two remakes of the divisive, experimental second entries of long-running Nintendo series on the 3DS - Fire Emblem Echoes: Shadows of Valentia, and Metroid: Samus Returns; taking their inspiration from Fire Emblem Gaiden and Metroid II: Return of Samus - both originally released in 1991. How these two games, from very different developers (Intelligent Systems, the studio responsible for the Fire Emblem series through its inception; and Mercury Steam, on their first foray into the Metroid franchise) variously approached their source material is interesting to compare and contrast.

SYSTEMS & GAME DESIGN

The first aspect which can be compared between the two is their take on the unique game structure and individual design decisions of the source games, as well as how they went about 'modernising' those quirks, both in relation to other entries within the series and the industry in general.

Echoes' faithfulness towards Gaiden's systems runs from broad design decisions - such as the near-exact replication of map design, focus on a world map structure, visitable towns and explorable dungeons - to smaller details such as magic being cast from health, the increased archer range (and 1-space counterattack) compared to the rest of the series, as well as broadly consistent statistical growth rates, the usage of an accurate instead of fudged displayed hit percentage (which the series abandoned in favour of the current approach with the GBA games), unique boss characteristics and weaknesses (the boss Jedah's having a specific order to which he must be attacked to receive damage, and the final boss falling to a specific low-level spell instead of the god-slaying Falchion) as well as the dread fighter to villager reclassing loop. The innovations and refinements to this structure were built on the base of surprising faithfulness to the original game - such as additional skills learned by classes or from weapons to add greater tactical depth to combat, boosts to the aforementioned statistical growth rates which still fell broadly in line with those of the original game, the inclusion of the 'Mila's Turnwheel' function which allowed player actions to be reversed to compensate for bad luck or hasty decisions, and inclusion of later series staples such as support conversations, playing without permanent unit death and base conversations. As such; while the game allowed for something resembling the original design philosophy of Gaiden to shine through, its faithfulness could also be argued to be a weakness - the extremely simplistic map design often cited as an example where a radical revision may have been in order.

Samus Returns can be compared along those lines - the 1991 original diverged from the first in the series through its focus on discrete, sequential areas over one continuous labyrinth, and structured itself around the hunt for 40 Metroids, the counter prominently displayed in the game UI throughout. These aspects were all reflected in the 3DS game, with additional refinements to bring things in line with modern series conventions - i.e., a map, diagonal aiming, fast travel and elevator cutscenes. However, on a moment-to-moment and core map design level, Samus Returns displays notable differences. Some of these disparities are purely to do with the technical limitations of the original title on the Gameboy - such as the zoomed-in field of view and monochrome palette, which give the original a specific, albeit unintended, atmosphere not shared by later titles. However, the fundamental flow of combat and navigation are also affected by three new additions new to 2D Metroid in general - 360 degree free aiming, Aeion abilities, and the melee counter mechanic. In particular, the early game encourages a reliance on the counter mechanic, with regular enemy health increased to match - this has drawn complaints for being a repetitive and obstructive gameplay device which needlessly slows the player down, but also praise for varying the strategy and pacing of basic gameplay from the now-staple 2D Metroid progression of beam spam to obliterating everything with the Screw Attack with little nuance in between. Likewise, the precision afforded by the aiming mechanic in boss fights and the way it forces a decision between movement and offense is a further tangible change in direction. Similarly, while hewing close to the original game's structure of linearly cleared, discrete sectors, the actual level design also displays changes in this regard - while maintaining the original's cavernous rooms in some respects, the freedom of movement with the wall-climbing Spider Ball is more often restricted, and paths are blocked with a higher degree of upgrade-specific barriers and blocks, along with an increased incidence of one-way or locked doorways. In this case, the deviation from the original while using the same base of ideas is apparent - the question more falls on whether the more focused and guided gameplay experience is superior - and in terms of the combat changes, whether the current approach offers a more enjoyable style of approaching the genre.

ARTWORK & ART DIRECTION

When comparing the artwork of the two games, the contrasting nature of the Fire Emblem and Metroid franchises is most apparent - as the former is largely not bound to the same set of returning protagonists and supporting cast members (with few exceptions), there exists a far greater scope for reinterpretation - particularly where Gaiden's rather amorphous and inconsistent designs are concerned. While references were frequently made to the original artwork, the sometimes-radical departures from the Gaiden sprites were near-unanimously seen as improvements - as the job here was to essentially create characters from whole cloth, rather than iterating on firmly established lines. Where a comparison to Metroid can be drawn is the way it interpreted the designs of its enemies and monsters - the Mogall and Necrodragon display conservative iterations on their original sprites and later series appearances, while the choice of a more conventional dragon form for the previously muculent Duma was still done within reasonable bounds of the established material, taking care to highlight his decayed nature and solitary laser eye.

These creature designs are similar to the revisions undertaken for Samus Returns' Metroid forms - notably present in the Zeta Metroid's shift from a squatter, bipedal form to a lankier distribution of the same features in a more xenomorph-inspired frame, and the Omega Metroid's shift to a sleeker body shape which notably reduces its oversized head seen in its cameo appearance as the 'final boss' of Metroid Fusion. Like the alterations to Duma, these design changes aid in presenting the creatures as more visually formidable antagonists (especially taking into account the more visible variance in size) - and while it can be argued that the new designs diminish some of the original material's uniqueness, they seem to generally be well-received as modernisations. The character design, as mentioned above, takes a completely different approach due to both the nature of the Metroid series and Metroid II's place within it - unlike Gaiden, whose characters remained mostly obscure afterthoughts open to complete reinterpretation, Metroid II defined the modern image of Samus, from the general shape and structure of the suit to the now-iconic Varia shoulder pads. As such, the task faced by Samus Returns was not one of reinvention, but embellishment. That can be seen throughout its designs for Samus - keeping to the established template of the character, while adding in various additional details and aspects taken from throughout the series - an iteration of the now-standard Zero Suit as it appeared in Other M with minor colour alterations being the most visible, but also a visor with the same profile as that of the Prime Trilogy's Dark Samus, Metroid Prime's blue-accented Gravity Suit, large visible treads for the Spider Ball and a denser distribution of light strips throughout the suit.

However, while the character designs may be conservative, the environmental art of Samus Returns displays a massive change. Return of Samus was a monochrome Gameboy title with essentially no background detail at all, while Samus Returns' most striking visual details are its colourful, vibrant and animated 3D backgrounds, leaning towards the bright palette of Zero Mission and Other M. The change in presentation (and especially atmosphere) cannot be overstated - the tone of the game completely changes when moving between the monochrome simplicity of the Gameboy and Samus Returns' approach. This is another area in which taste can be seen to differ - while the increased visual feedback and interest of these additions is essential for a modern title, the degree to which they provide a livelier and brighter take on SR388 is considered a step down for those who found the original's limitations created a memorably tense and dread-filled experience.

MUSIC

Title (Metroid II) / Title (Metroid II)

Metroid Boss (Metroid II) / Omega Metroid (Samus Returns)

Chozo Ruins (Metroid II) / Chozo Ruins (Return of Samus)

Queen Metroid (Metroid II) / Queen Metroid (Samus Returns)

Vs. Duma (Gaiden) / A Fell God's Tempest (Echoes)

Land of Sorrow (Gaiden) / A Song for Bygone Days (Echoes)

Tower (Gaiden) / The Pinnacle of False Belief (Echoes)

Final Map (Gaiden) / Twilight of the Gods (Echoes)

Metroid II's soundtrack may be more of an outlier among the larger series than even its general structure and presentation - eschewing the melodic and memorable background tracks the series is known for, its area themes largely trend towards ambience and border in places on atonality. While Samus Returns does feature several arrangements of Metroid II's music, such as the 'Tunnel' theme, an atmospheric take on the Chozo Ruins track and a cover of the Baby Metroid theme, it largely deviates from the Metroid II soundtrack, whether with original material or covers of tracks from elsewhere in the series - prominently using the Lower Norfair, Theme of Samus and Brinstar (Red Soil) cues as well as the expected Ridley boss theme; in addition, the game's version of the title theme foregrounds the original Metroid theme before including elements of Metroid II's own title theme. Considering the nature of Metroid II's music, this liberal approach making significant use of popular tracks from the rest of the series would seem to be justified in pursuit of producing a recognisable 'Metroid' soundtrack - while also retaining some elements of the original game's approach in the use of primarily atmospheric music.

Fire Emblem Gaiden's soundtrack was not nearly the departure from series standards Metroid II's was, and as such integrating it into a modern remake in line with recent franchise games was not as difficult a task, however the comprehensiveness of the approach taken towards the original soundtrack is an interesting contrast. No tracks from the original game were left out, regardless of their seeming incompatibility with the most recent games in the series - such as the use of several distinct world map themes when compared against Fire Emblem Awakening's short world map jingle and Fire Emblem Fates' silent world map, the return of separate battle themes after Awakening and Fates' adoption of dynamic music; and retaining the final boss' chaotic map theme-interrupting track as opposed to going with playing a single map theme throughout as with both aforementioned games. Also worthy of note is the way in which Echoes builds on the leitmotifs of the original Gaiden score alongside original music, most notably in 'Lord of a Dead Empire' and 'Sacrifice and the Saint'.

Meanwhile, Samus Returns' more distant relationship with its source material results in several pieces from Metroid II being left out entirely, and avoids turning the original soundtrack's themes into longer-running leitmotifs through its preferential use of motifs established elsewhere in the series. This lack of 'faithfulness' is by no means a negative thing, however, as it does allow the game more freedom in terms of sound design, while decisions such as the use of a separate battle theme in Echoes could frequently feel like a pointless step back, a replication of tradition for tradition's sake. Original themes for each Metroid form further accentuate their progression, and while the use of music decoupled from individual areas (e.g. Lower Norfair in every superheated room) is a significant departure from previous games, it does fit Samus Returns' reduced emphasis on backtracking and effectively stage-based design which leaves less room to intimately characterise each area.

NEW STALKERS & OLD RIVALS

As a final point, both games' handling of a storied remake expectation - entirely new content and series continuity - serve as an interesting parallel. While as a RPG, Echoes' far more present storytelling and full voice acting can't be compared to a story-light Metroid title through basic structure, the way these additional elements are introduced in relation to the original games does create an interesting contrast. Along with new threats throughout the main bulk of the storyline (the ever-present Diggernaut in Samus Returns, the new antagonist Berkut in Echoes) and backstory additions in line with series mythology (the clarification of Mila and Duma's nature as Divine Dragons and the looming threat of Grima; plus his newly created backstory, alongside the references to Metroid Fusion's X in Samus Returns, as well as the ominous introduction of the Chozo civil war) Echoes and Samus Returns also feature a final 'bonus' boss who appears elsewhere in the series - for Echoes, a nascent form of Fire Emblem Awakening's Grima, and Samus Returns the near-omnipresent Ridley.

Where this differs most is in how this element is treated - it is impossible to fight Grima in Echoes before the credits run, and the 'Labyrinth of Thabes' in which he appears is firmly treated as a dubiously canonical postscript. Meanwhile, Ridley's appearance in Samus Returns is a mandatory part of the finale - he's now the actual final boss; not an extra challenge for a higher difficulty mode, certain completion time or percentage. It's a fascinating difference in how Samus Returns and Echoes exist in relation to their source material that a game far lighter on story content and additional narrative is the one which made the decision to make such a central change.

In any case, Samus Returns did get away with a much neater title - "Fire Emblem Echoes: Shadows of Valentia" will always be a mess.